MARYSVILLE – Being foster parents can be maddening – like when one kept running away. She wants to come back now, but she’s in a group home.

“She calls me every night and tells us how much she loved us, but didn’t realize it,” Sheri Paquette said.

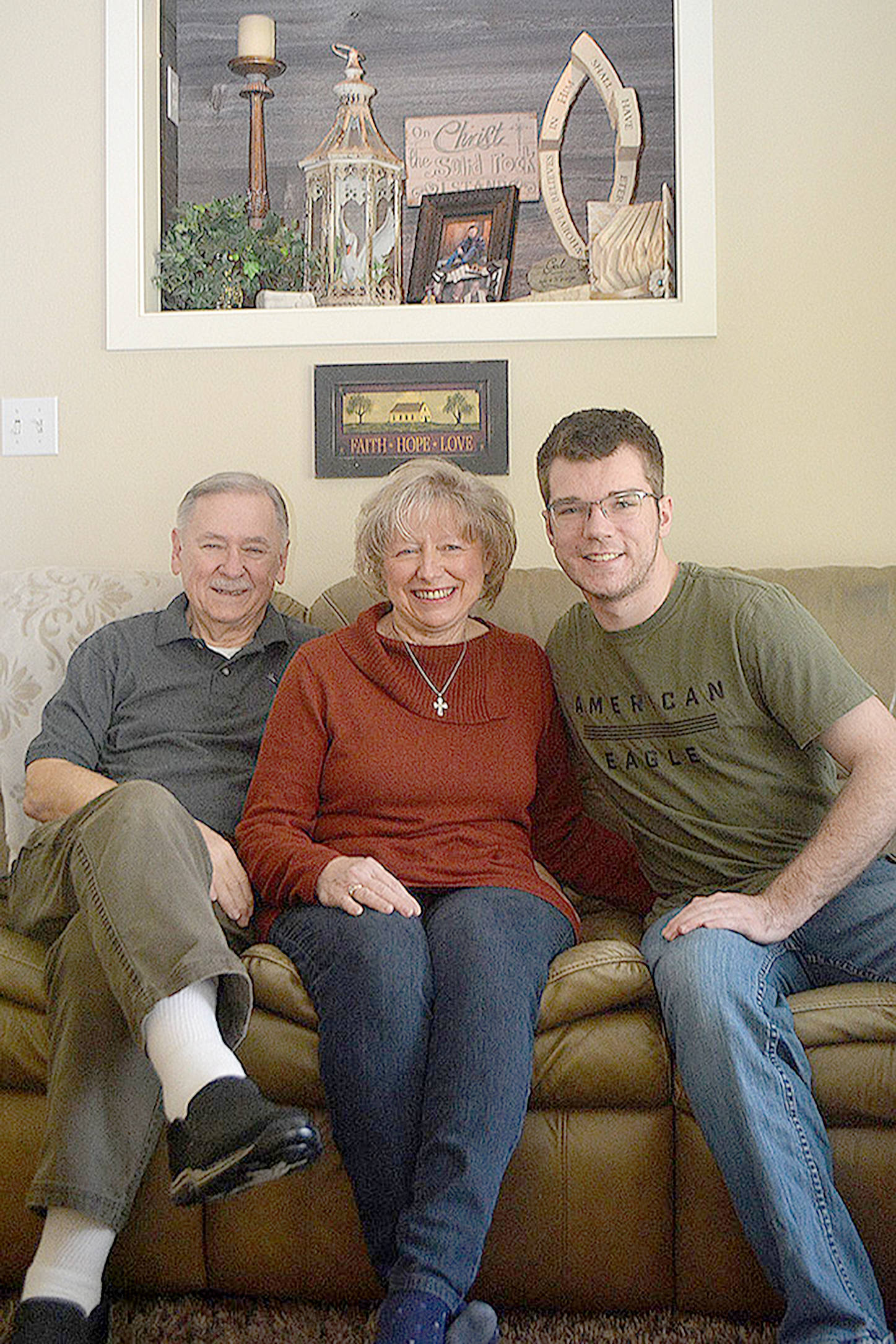

Sheri and her husband, Don, have been foster parents for 15 years, much longer than most.

Of course being foster parents can be spectacular, too. For the Paquettes, that’s been watching the progress made by their adopted son Matthew the past four years.

He first came to them at age 15. They adopted him at 17. He’s 19 now.

Matthew, who is autistic, had been adopted before and been in numerous other foster homes before being placed with the Paquettes.

“It was the best thing that ever happened to me in the foster care system,” Matthew said. “I got through high school because of them.”

Matthew didn’t like school. He certainly never thought he would go to college. “He was always told how stupid he was,” Sheri said. But they were determined to help him succeed. “If you want to make a difference in someone’s life fostering is where you need to be,” Sheri said.

She still works as a pastor at a Church of God in Everett, but Don is retired from Boeing. “He didn’t know what homework was,” Don said, adding getting Matthew focused on that was a key to his academic success. Matthew now attends Everett Community College.

The Paquettes didn’t get into fostering to adopt. “We’re too old,” she said.

But it was the right thing to do with Matthew. “He’ll probably be with us forever,” Sheri said. For someone who wants to adopt, fostering is a great way to go. Then you get to know the child first. “I could not push that more,” Sheri said.

Fostering is no different than being a regular parent, she said. “Your life is no longer yours,” she said. “It’s about that child. You have to help children realize they are valued, important and special.”

Support is key

Sheri said one of the reasons they’ve been fostering so long is they have a lot of support from a group called Mockingbirds. When “life happens” and they need someone to watch their kids, they can call someone in the Mockingbird group to help.

“They get to know other foster kids,” Sheri said. “It’s kind of like family.”

She doesn’t think she and Don could have lasted so long without that help.

“It’s sad. A lot of people don’t make it through their first year” of fostering, she said. Sheri said it’s a worldwide model, with people from Canada, Japan and England coming here to “see how our group works.”

She said the foster system needs more groups like it.

“It’s a constant circle thing,” she said. “The state wastes so much money on training. We lose good foster parents because they don’t feel they have the support.”

Starting out

The Paquettes got started fostering when a son got into addiction, their grandchildren were taken by the state, and, “We stepped up,” Sheri said. When their son got his life in order and got the kids back, they decided to keep at it. She said they were “surprised” when they got that first child.

“It’s different from your grandchildren,” she said. “We’re responsible for a stranger’s child.”

She was 3 and “the cutest little thing ever.” However, she had “issues,” and they weren’t told what they were.

It was her 10th foster home that one year.

“How hard could it be? There’s two of us and one of her. She taught us well,” Sheri said. “It took us a good year to find out her issues.”

They had her for 2 1/2 years and came very close to adopting her, she said.

“She’ll always be a part of our hearts,” Sheri said. One of the hardest parts of fostering is letting go. “A lot of people can’t do that,” she said. Sheri said the girl was adopted by a wonderful family. “We had to really back away from her. It was a difficult transition for her” too, she said.

She said they keep fostering because there are so many kids who need help.

“There’s always more. Stories that break my heart,” she said. “It’s hard on us to see what the kids go through. We just can’t stop.”

Other issues

Dealing with parents can be an issue. They have to realize you’re not trying to take their children, you’re just trying to help.

“Bio parents get angry with you because you get to do what they want to do,” she said. “You become enemy No. 1. That’s OK because it’s for the kids.” Foster kids are angry, too. But two have come back with their parents and said they appreciated us, she said. The biggest problem is social workers with caseloads that are too big.

Matthew went through a number of case workers himself. “I’ve seen a lot of binders,” he said, “A lot of binders with my name on it.” When the runaway girl mentioned earlier couldn’t be found, the Paquettes couldn’t reach the case worker. “This is what foster parents struggle with,” Sheri said. “I panicked. I called police.” But that wasn’t an isolated incident. She said caseworkers often don’t get back to her for a week. “It immediately goes to voice mail,” she said. “I’ve lost it before with them.”

Because they are under a lot of stress, caseworkers often don’t last any longer than foster parents.

“We had a teenager for fifteen months who had four social workers. Case workers need to have the time,” she said, adding they work 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. while foster parents work 24 hours, seven days a week.

Foster parents end up figuring a lot out on their own, but the Paquettes still try to keep good rapport with case workers. “You get a whole lot more done that way,” she said.

Sheri said she gets frustrated and cries a lot, but just keeps remembering it’s for the kids.

“It’s not something you’re going to get a lot of pats on the back or high five’s for,” she said.

————

Fast facts

•The Department of Children, Youth & Families reports there are 91 licensed foster homes in Arlington and Marysville. Their Smokey Point office has 197 children getting care, many with family members.

•In Snohomish County there were 534 youths removed from their homes in 2018, and 826 children lived in out-of-home care.

•Children in Washington state spend more time in foster care than in 46 other states.

New law?

Treehouse, a statewide nonprofit that Sheri and Don Paquette are part of, says the state legislature must invest in more caseworkers to reduce caseload sizes and provide more stability. High caseload sizes lead to poor case management, high staff and foster parent turnover, lower rates of family reunification and an increased stay in foster care. Treehouse is urging the legislature to add 20 caseworkers. “The caseworker is the most critical investment the legislature can make in the success of families and children in the child welfare system,” Dawn Rains of Treehouse said.

Forty-three percent of state caseworkers have caseload sizes exceeding 20 youth or more, with some as high as 30. Best practice recommends no more than 15.

Treehouse also is advocating to pass a law to achieve educational parity for these young people by 2027. Also, 40 percent of the youth Treehouse serves depend on special education services. Treehouse is asking the legislature to better support kids with high mental, behavioral and developmental health needs; ensure equitable funding for special education; and lower the student-to-school-counselor caseload to a minimum of 250 to 1.